Kizzie Dishman

before 1755 - after 1840

Alternate Names: Kizzy, Kizey, Keziah, Kirsiah, Kezekiah, Dishmon

The following article quotes historical sources that may portray demeaning stereotypes and attitudes.Kizzie Dishman is the first known descendant of the Dishman family line originating in Iredell County, North Carolina. She’s an interesting family member to research due to many unproven claims concerning her Cherokee heritage and family connections.

Some accounts argue Kizzie was a relative of the infamous Chief Doublehead, while others claim she had no Cherokee ancestry at all. The following article explores what official documentation we have pertaining to Kizzie and her relatives, and what information is most likely fiction.

Land Grants, Acquisitions, and Sales

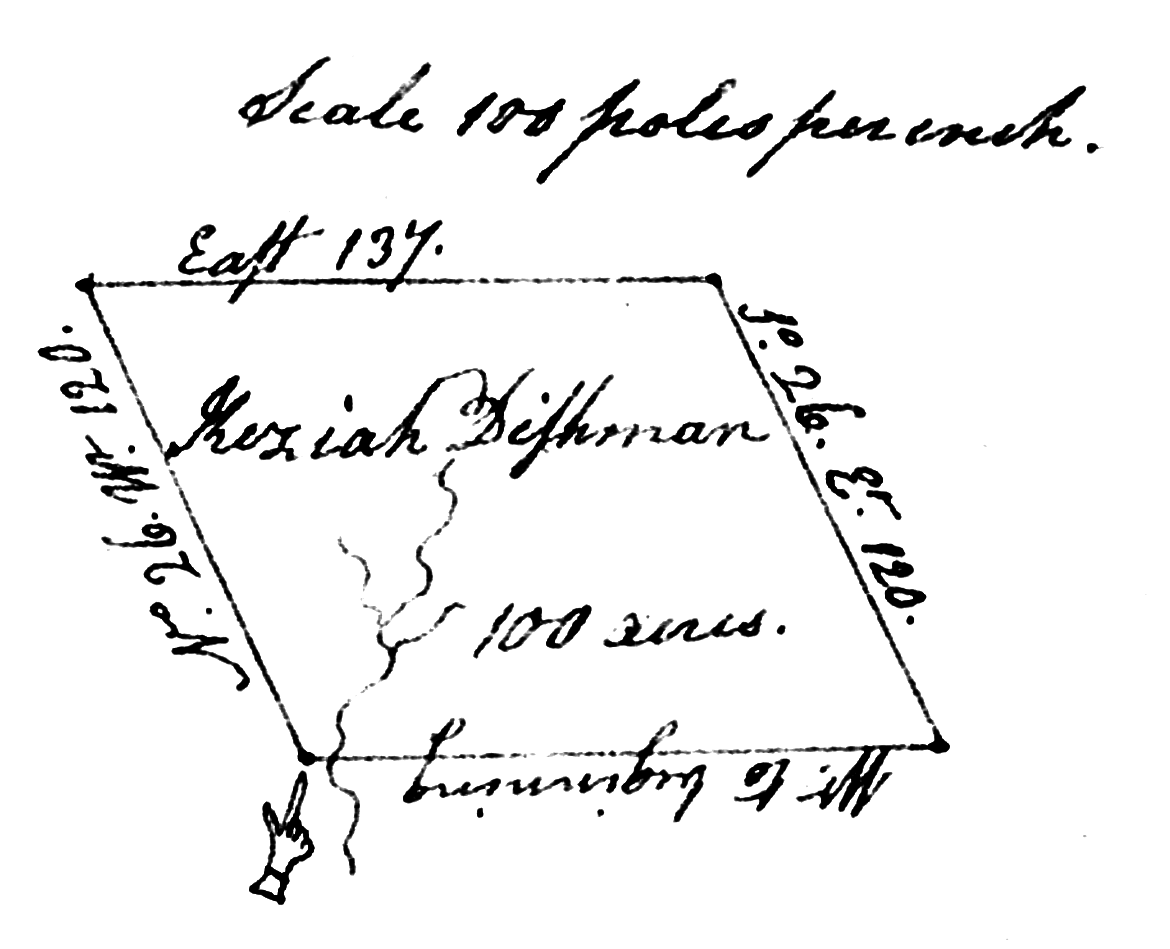

The first official information pertaining to Kizzie is found in a 100 acre land grant dated 1798 located in Iredell County, North Carolina. Five years later, in 1803, she sold this land to one of her three sons, Lewis Dishman [1].

Map of Kizzie Dishman's 100 acre land grant located in Iredell County, North Carolina. Resting at the dropping off branch of Rocky Creek. [1]

Map of Kizzie Dishman's 100 acre land grant located in Iredell County, North Carolina. Resting at the dropping off branch of Rocky Creek. [1]

Census Data

Census data prior to 1850 lacked age specificity for family members and only listed the head of household by name. This makes calculating the Dishman family birth years a bit of a guessing game.

In “Kizey” Dishman’s 1800 Iredell County, North Carolina census record [2], her household consists of one male under age 10, three males age 16 to 25, one female age 16 to 25, and one female age 45 or older.

This means the earliest Kizzie could have been born is 1755. We can also assume the three males between age 16 and 25 are her three sons; Jefferson, Lewis, and James. In addition to this census record, there’s also a letter written in 1905 confirming three men are brothers. [8]

By the 1810 census, “Kirsiah” was living alone [2], presumably her sons were all married and beginning their own family lives.

All of Kizzie’s household members, including herself, are listed with a race of “white” in the 1800 and 1810 census records, a suspicious entry that contradicts her assumed Cherokee heritage. We’ll explore Kizzie’s Cherokee claims later in the article.

Thomas Dishman

There are some accounts of Kizzie marrying a man named Thomas Dishman, supposedly a son of Peter Dishman and Sarah Reynolds of Westmoreland County, VA. However there are no known records to confirm a relation between Peter and Thomas, or any documentation linking Kizzie to Thomas.

In the 1800 census, Kizzie was on her own as head of household [2], so Thomas had either died, deserted, or was nonexistent. Unfortunately, Iredell County marriage records prior to 1851 were destroyed in a fire [3], and there is no official information found in local newspapers or family documents to corroborate their marriage.

There are however some personal accounts supporting Thomas’s existence. In letter from Nellie Mae Crouch to Robert Phillip Upchurch discussing Dishman oral history, Nellie describes her family’s narrative concerning Kizzy:

“The story which some of our Kentucky relatives told us was that Jefferson Dishmon was the illegitimate son of Tommy Dishmon and a full-blooded Cherokee Indian girl named Kizzie. The lady said that this couple married when the boy was two years of age. - Nellie Mae Crouch [4]”

This same narrative is also echoed in a bulletin by Barbara Morris. [9]

Whether or not Kizzy’s husband, Thomas, exists is a family tale, and unfortunately cannot be confirmed.

Kizzie Moves from North Carolina to Kentucky

Between 1810 and 1820, Kizzie’s son Jefferson and his wife Lydia had relocated their family west to Wayne County, Kentucky. [5][8] Kizzie reportedly followed them some years later, although she disappeared from the census records. We can confirm Kizzie’s move from North Carolina to Kentucky via witness accounts attached to the Guion Miller Roll applications of Kizzie’s descendants. According to Sam Abbott, a Dishman family friend, Kizzie came to Wayne County sometime around 1840. [6]

Others argue Kizze joined her son Jefferson’s family on their initial move from Iredell to Wayne. In a letter from Betty Dishman Gross to Phillip Upchurch, She describes a narrative reportedly shared by her grandfather, Burl Dishman. [10]

“...Jefferson and Lydia Dishman came to Wayne County, Ky from North Carolina with nine or ten little Indian babies and an old Indian woman.” - Betty Dishman Gross [10]

Cherokee Heritage

Before looking into the details of Kizzie’s heritage, we first must address the possibility that her alleged Cherokee lineage is purely based on family legends originating from cultural shifts of the American south. White American families claiming a Cherokee ancestor, typically a grandmother figure sometimes referred to as a “Cherokee princess”, is a common assertion. [13] Most of these claims are unsubstantiated and lack documented proof despite the numerous Cherokee rolls implemented by the U.S. government between 1817 and 1924. [11]

How exactly did this trend begin?

The “Cherokee Princess” trend began soon after the 1838 forced relocation of the Cherokee people, more infamously referred to as the Trail of Tears [17.1], as white southern culture flourished with the recent expansion of territory. Native names for towns, landmarks and other locations were adopted in these newly absorbed lands, heightening white southerners' sense of regionalism. In tandem with the influx of a Native American presence in Anglo-American literary genres, white southerners began to believe they were “destined to prevail” against their honorable Cherokee foes. [13] Having once despised the Cherokee and other native groups, white southerners had begun to romanticize Native American figures. Rumors of a long lost “Princess” Cherokee ancestor became intertwined with reality in the oral histories of white families, giving them a sense of connection and royal entitlement to the land they now inhabited.

Why is there an abundance of unproven claims specific to the Cherokee tribe over any other Native American group?

While there are many incorrect claims of a Cherokee predecessor in white families, that doesn’t necessarily make them all fictitious. The Cherokee nation was (and is still) one of the largest native groups in North America [17.1], with lands that originally stretched across eight modern day southern states. [12] Upon initial contact with colonists, they were incredibly open to intermarriage and often used it as a diplomatic tool. Scots-Irish traders were even told marriage to a Cherokee woman was a requirement in order to live on Cherokee land. [14] In traditional Cherokee society, husbands moved into their new brides households, but by the 18th century British influence shifted local customs as Cherokee women began to move into their white husbands’ homes and adopt their last names. [14]

Map of Cherokee lands; Original limit, post Revolutionary War, and Final Cession. Iredell and Wayne counties, homes of Kizzie Dishman, and Chief Doublehead’s village circa 1800 are also marked. [12]

Map of Cherokee lands; Original limit, post Revolutionary War, and Final Cession. Iredell and Wayne counties, homes of Kizzie Dishman, and Chief Doublehead’s village circa 1800 are also marked. [12]

Is Kizzie a casualty of the “Cherokee Princess” Syndrome?

So how do we know if Kizze’s Cherokee claims are fact or fiction? Most of the accounts concerning Kizzie’s heritage do come from oral histories, such as Nellie Mae Crouch’s letter quoted above. In addition, I have personally heard accounts of the stereotypical “Cherokee Princess” from both my mother and great-grandmother. Fortunately, some written documentation exists that can provide a more accurate picture.

Evidence & Guion Miller Rolls

As mentioned previously, Kizzie’s census records list her race as “white”. [2] Since the majority of Native groups at this time did not live under U.S. jurisdiction, the federal census only offered “white” and “colored” as options for race. Her being marked as “white” on both the 1800 and 1810 census does not necessarily rule out her supposed Cherokee ancestry. What’s most confusing is that she was recorded on the census at all, especially without a corresponding white husband. If Kizzie was Cherokee, that means she had abandoned her nation in favor of raising her children alongside the encroaching colonists.

The most supportive evidence in favor of Kizzie being Cherokee comes from the Guion Miller Rolls. In 1902 the U.S government lost a lawsuit for the violation of Cherokee agreements, and were ordered to provide Cherokee families a one-time payment. The resulting rolls contain a detailed list of applications for the aforementioned funds that claimed they or their ancestors were of the Eastern Cherokee tribe and were directly affected by the forced removal of 1838. [11] The Dishman family claims were ultimately rejected, but they still provide a detailed list of family relationships and personal accounts.

We know Kizzie moved to Wayne county around 1810 or 1840 due to Sam Abbot’s witness statements [6] and Burl Dishman's [10] oral histories.

Sam Abbot's account offers an outside perspective of the Dishman family, and was attached to the Guion Miller roll application of one of Kizzie’s great-grandchildren, Jefferson Dishman son of Archibald Dishman. Kizzie and her family's relocation is suspiciously close to the Cherokee removal of 1838 - perhaps she thought the Cumberland mountain region a safe place to hide from removal officials?

Below, Abbot describes her supposed Cherokee ancestry.

“I was personally acquainted with Kizzie Dishman. I have heard her say many times that she was an Eastern Cherokee Indian of full blood … She possessed all the traits, habits, and fashion in dress, actions, and deeds of an Indian. She was of a dark yellow complexion, small in stature with straight black hair and dark black eyes.” - Sam Abbott [6]

Furthermore, an account by Sarah Upchurch describes Archibald Dishman, Kizzie’s grandson, as referring to himself often as the “yellow man”. [6] This suggests that Kizzie’s professed Cherokee heritage was not taken seriously by her grandchildren, a logical conclusion for a family raised entirely in white culture.

There are 68 known descendants of Kizzie, spread across three generations, all claiming Cherokee lineage on the Guion Miller Rolls. [7] Despite the numerous descendents asserting a connection to the Eastern Cherokee tribe, there is still a chance these applications could be a money grab. In particular, Milly Vaughn, a third great granddaughter of Kizzie, wrote to the Guion Miller commission ten times in the course of a year begging for, and occasionally demanding, a payout she felt entitled to but would ultimately never receive. [6]

Doublehead Doubts

One of the more interesting arguments pertaining to Kizzie is that she is somehow related to the infamous Chief Doublehead. Doublehead was well known for his violent raids against encroaching white settlers of the Tennessee Valley. His war parties terrorized the region for roughly 20 years between 1775 and 1795. He was notorious for scalping and mutilating his enemies, and in one instance even engaged in cannibalism. His murderous actions were not limited to colonists however, as he had beaten two of his own wives to death. Later in life, the raids stopped as he pursued business interests and participated in questionable land deals with the U.S. government. By 1807, the Cherokee had become fed up with Doublehead’s brutal actions and corrupt dealings and orchestrated his assassination. [15]

In Rickey Butch Walker’s book, “Doublehead: Last Chickamauga Cherokee Chief”, he discusses in detail many of Doublehead family relations. He mentions a child of Doublehead “Kstieieah Keziah” who married a man named Thomas Dishman and was born circa 1775. [15] This cannot be correct, since the census records indicate Kizzie was born prior to 1755. Walker himself warns readers much of the family information provided is based on folklore.

Some accounts claim Kizzie is instead a sister of Doublehead, and both share Willenawah Great Eagle as a father. This also seems unlikely, as the only documentation potentially linking Doublehead to Kizzie is found in Catherine Spencer’s deposition concerning her uncle Doublehead’s estate. [16] In the deposition, she mentions an aunt by the name of Kstieieah with no corresponding surname. This entry is instead most likely referring to one of Doublehead’s wives, Kateeyeah Wilson, not Kizzie Dishman.

Catherine’s testimony relates to events that took place at Doublehead’s plantation shortly after his death in 1807. Doublehead’s village was located in what is now northern Alabama [12], quite a distance away from Kizzie’s Iredell county, North Carolina residence.

There are some claims of Doublehead being buried near Kizzie and her family in Dishman Cemetery. [9] These accounts are fictitious, as Doublehead was likely buried in an unmarked grave near his home in present day Lauderdale County, Alabama. [12]

Limitations of DNA

Unfortunately, there are no certified Cherokee DNA tests available for Kizzie’s living descendants to take. The typical technique for creating a DNA comparison requires samples from “ethnically pure” individuals. This is a difficult task for any American indigenous group due to the abundance of intermixing with Europeans. Essentially, getting a DNA profile of the Cherokee tribe before Spanish conquest is unlikely. [17.2] As technology continues to improve, perhaps a solution will be discovered that will easily prove or disprove the abundant “Cherokee Princess” claims.

Conclusion

Despite the witness accounts of the Guion Miller Rolls, we still can’t be 100% certain Kizzie was Cherokee. While it’s unlikely these accounts were fabricated, it’s not outside the realm of possibilities. We can’t be sure of her heritage without new found documentation or possibly an improvement in indigenous DNA profiles. Regardless of her background, she is considered the first traceable ancestor of the Dishman line originating in Iredell, North Carolina and her story gives us a personal perspective of American history.

Death & Burial

We're not certain when Kizzie died, but she's reportedly buried in Dishman Cemetery in an unmarked grave. This cemetery is not far from her son Jefferson's land on Otter Creek.